SECTIONS

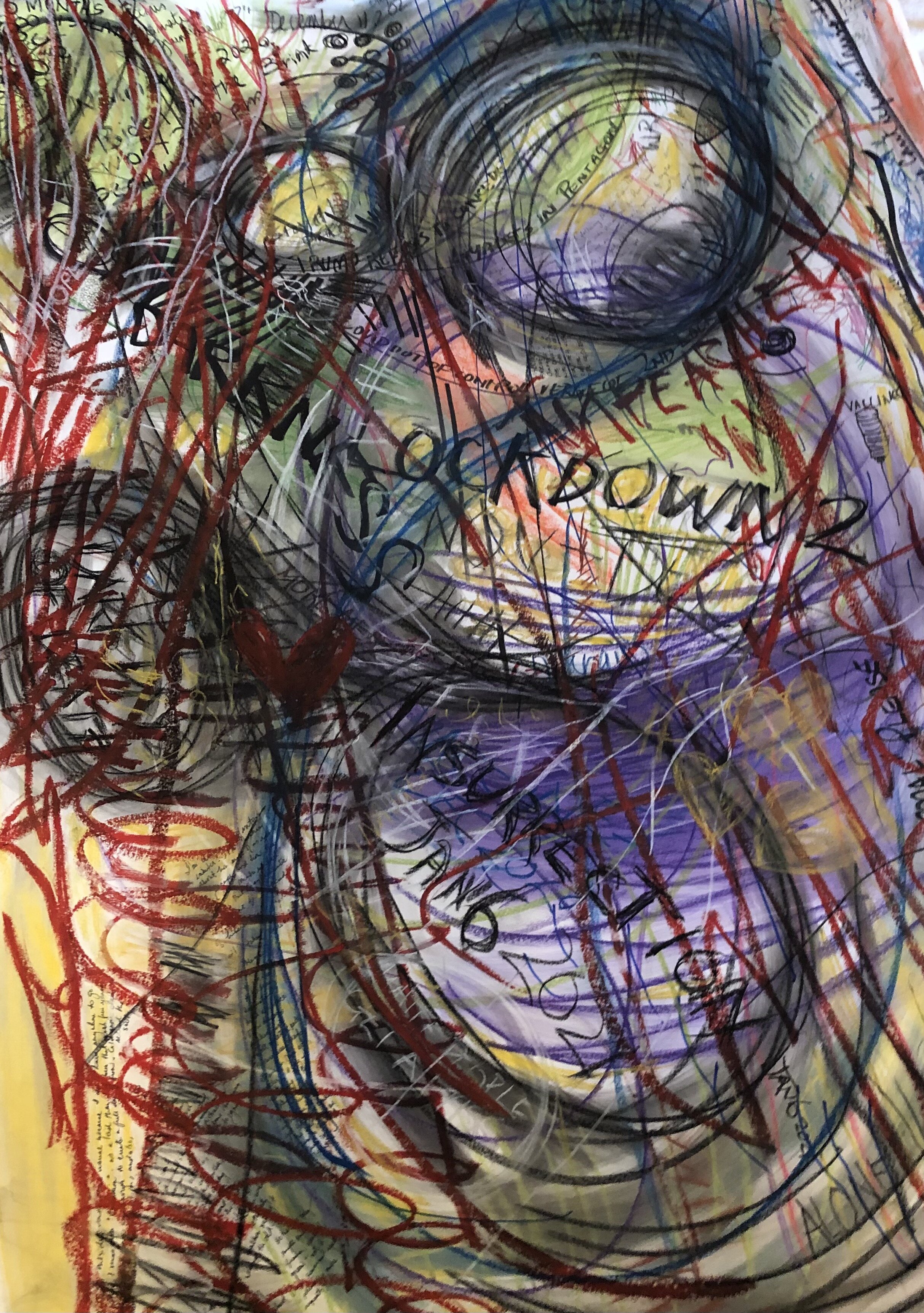

Pandemic Paces

Poet Trees

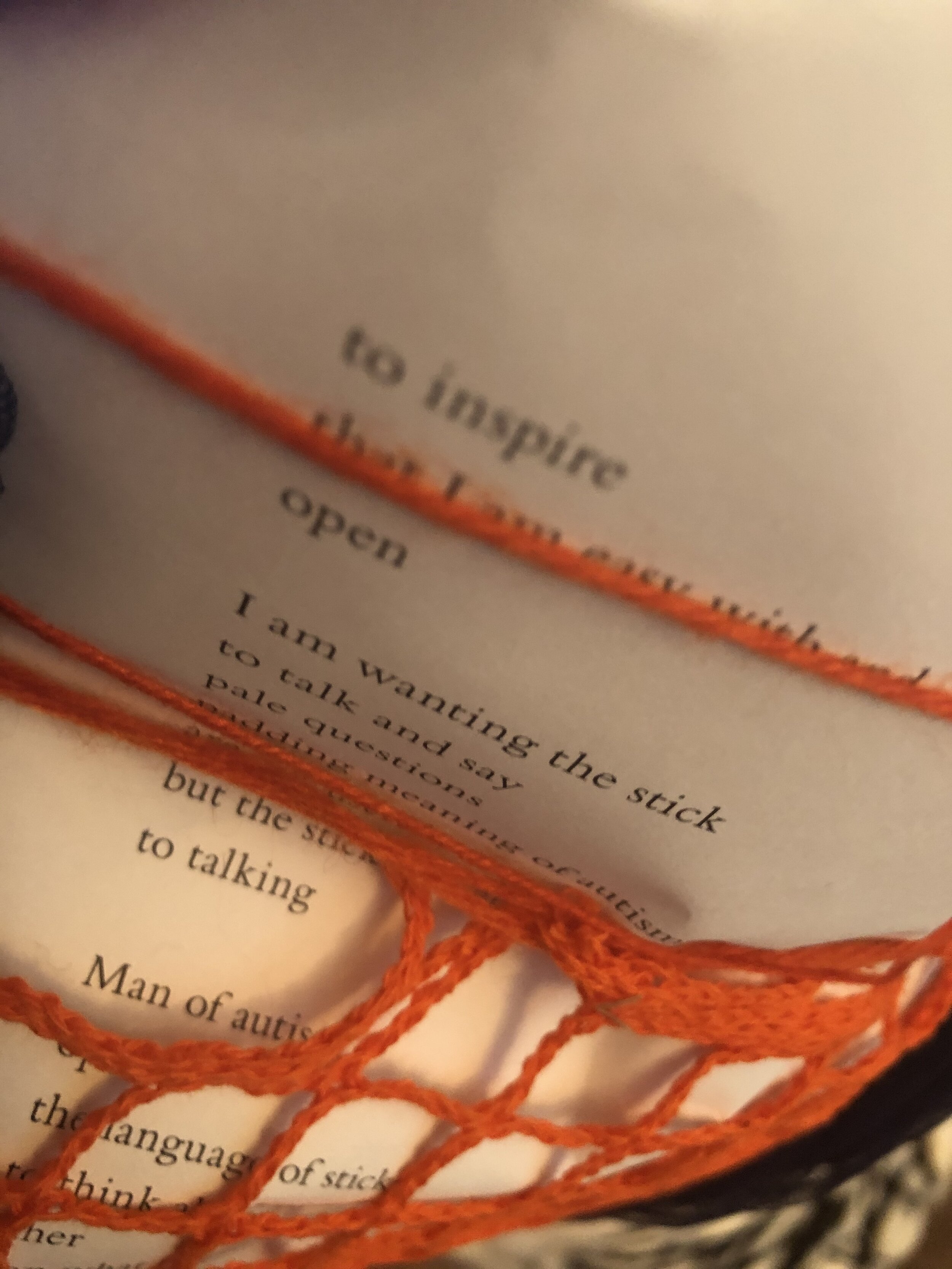

Pandemic Paces - Estee Klar with Adam Wolfond

During lockdown, many of us commented that we had the time to find our own pace. We reflected on the hubbub of our lives; the rushing, the relentless hours and time away from our families. Slowing down reminded us how we need to be versus what neoliberal system has urged us to become.

Adam Wolfond, a non-speaking “man of autism” as he names himself, thinks a lot about pace - keeping pace, making pace, tapping pace and the pace of the atmospheres. For Wolfond, keeping pace is both pleasurable and adaptive – attuning to the many ecological paces that “call [his] body to “answer.” In our collective work, we consider neurodiverse pace to reveal the neurodivergent city; the conditions that support neurodiversity and also, how we study and collaborate together.

Rhythm and pace create space. Architect/philosopher/artist/ Madeline Gins suggests that, “[our] sense of space is determined by the practices we grow used to” (1994, 28). Brian Massumi writes that, “[h]abit adds to reality” (2002, 151). Think of a tic, a twirl, a hesitation as co-composing movements in “the city of moving parts.” Is s/pace fixed and situated, or shifting as we move? Movement diversity reorients our space. Repetition, humming, sideling glances, twallowing, stimming are ways of orientation and perception. (Note: twallowing is a word Wolfond invented for shaking a stick. Stimming is a reclamation of the behaviourist reference “self stimulatory behaviour.”)

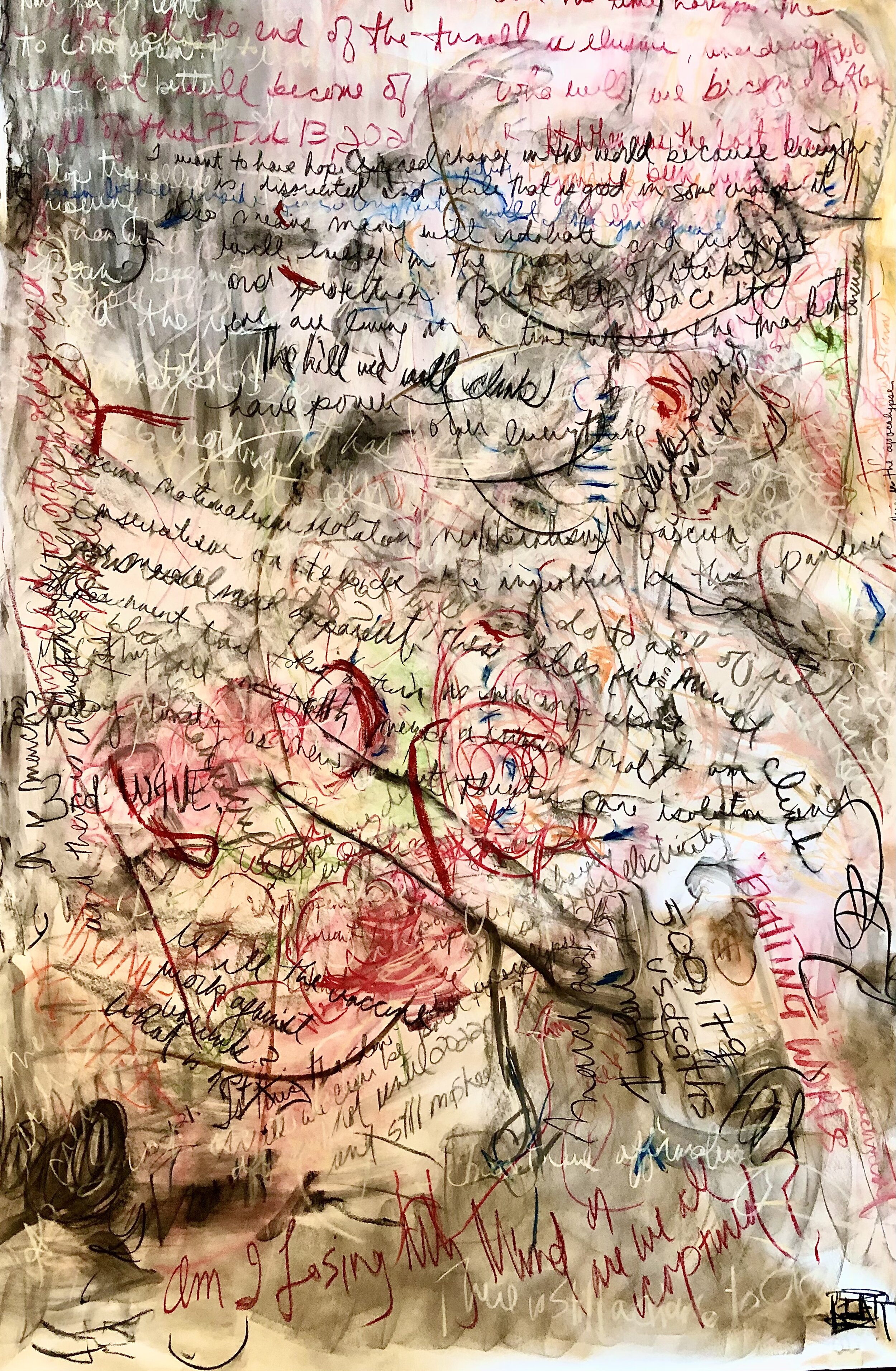

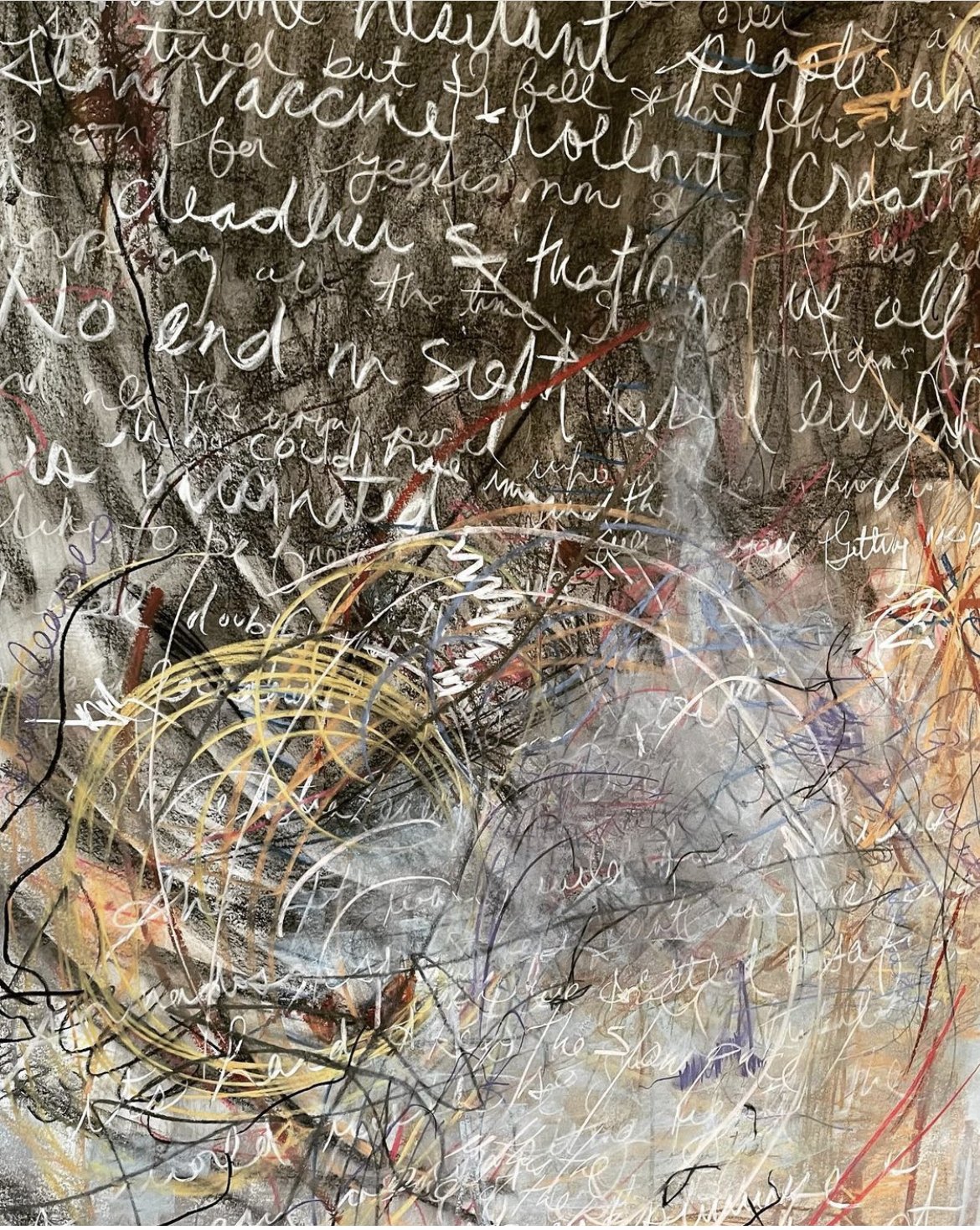

For Wolfond and many autistics, space is like an open field full of forging details, coming at a rate that not everyone imagines. Unlike neurotypical perception that can subtract detail from the environment/space more easily, autistic perception, particularly among non-speakers, is additive, open and busy, expressing in a different array of somatic movements. Sadly, these autistic moves are characterized as disordered in the clinical fields. Yet, Wolfond conceives of a way of movingrelating, thinkingfeeling in the world that he names “languaging”, and suggests that there are variety of paces that help him move within it. This movement includes the act of writing which is always in relation with the non/human paces; the ecological milieu. At our Collective, our discussions around perception, poetry, pace and relation moves us to experiment to engage in collaborations that rethink support, care and creation.

As a facilitators and collaborators, we attune to the world that neurodiversity generates. Neurodiverse perceptual differences bring forth an understanding of diversity within the human species. This diversity, which includes intersections with sexual orientation, religion, race, ethnicity, also includes the array of perceptual experiences we encounter as humans, and also, within a more than human world that, as it happens, also needs urgent attention. Autistic perception dances these relations, bringing new understandings forth, relanguaging without references to the pathology paradigm.

Ticcing, stimming, flapping, humming are ways in which we dance the world into existence, what Wolfond calls “a dancing for the answering.” It is not exclusive to autistic people and culture that there is a different way of perception and orientation. There are many manifestations of perception among us. We wonder how, still, after more than 20 years of the neurodiversity movement, that many still cannot conceive of autistic culture as important, with an indigeneity that sadly continues to be devalued.

To this we wonder, how many ways is the world?

How is neurodiversity?

A diversity of perception and pace means also that we must all enter relationships with a non-hierarchical mindset. Too often, autistic people are taught to comply and conform to neurotypical ways of moving and learning which assumes that there is only one way of orientation and understanding among us. This imposes a force that is oppressive to many autistic people.

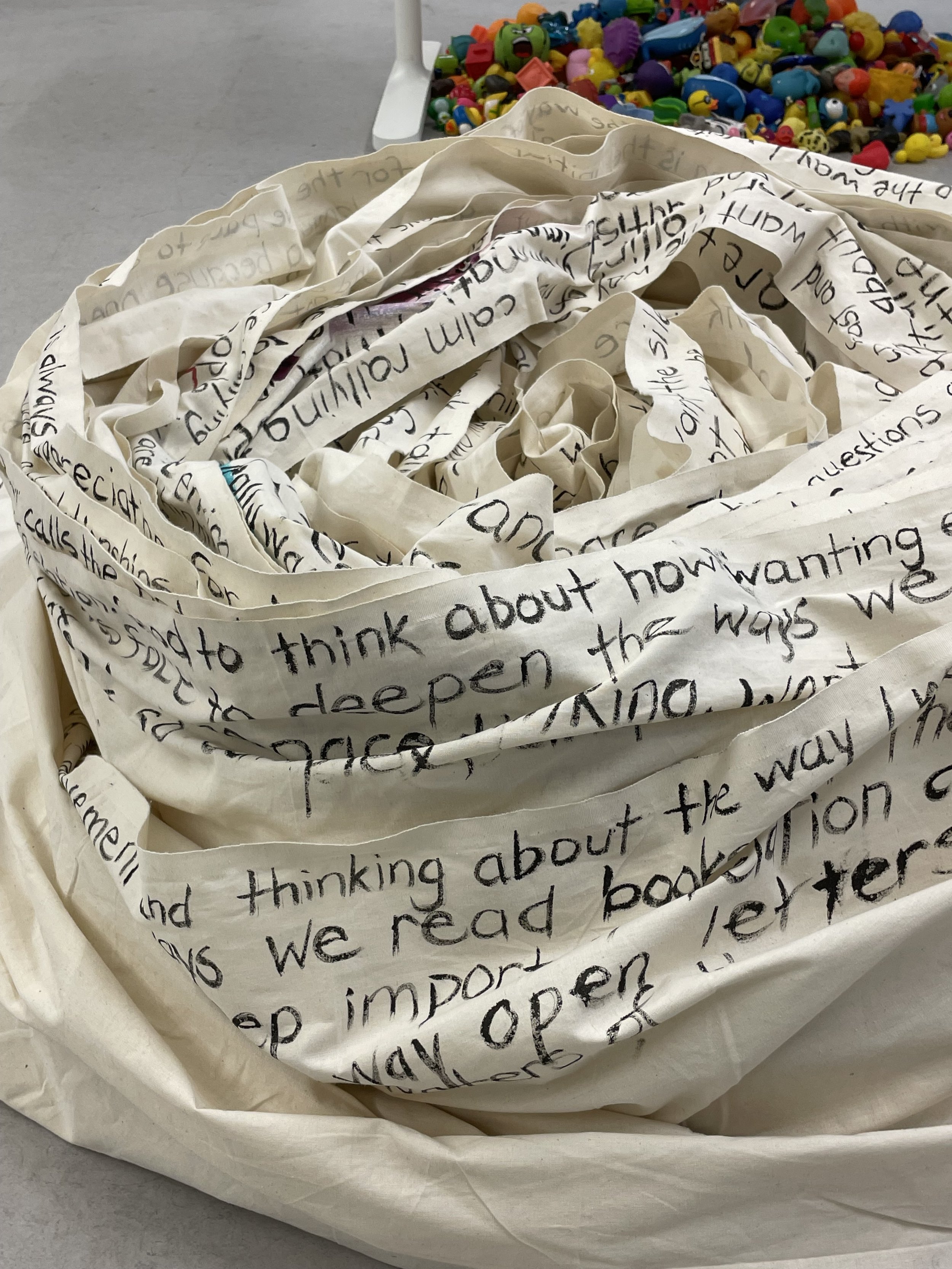

There is a difference between the support relationships versus a clinical and pedagogical practice of compliance and conformity. To be with diversity is to take our time, to rethink and subvert the demands of neoliberal and linear time, to be in our own time, and most importantly, to have this space and time to discover how we can support neurodivergent ways of being and creation as it emerges without the imposition of westernized cultural systems and forms. We need new forms and ways of moving and engaging with the world! In our studio, we allow ourselves to lie down when we learn, to move, to tap a rubber bath toy. How we can be together is what’s at stake – as opposed how we ought to be and work together - and to be in relation can take many forms. It need not be in a self-same pace, sitting still on a chair, or by speech alone. To be with diversity we need to attune also to the atmospheres that call forth a more complex perception that exists beyond the individual human body.

We are especially interested in non speaking autistic writing and creation for it is typically categorized as “severe autism” with an assumption that this cadre of autistic people cannot process, think and function in the world. And it is true that many people need more daily support which we urge, requires more robust understandings of neurodiversity from autistic people.

Many non-speaking poets and writers learn to use alternative forms of communication through hard work and relational support that is referred to as facilitation. Supported typing and communication is often criticized for having the need of another support person. Our society tends to value the independent artist/writer as the master of their “own” work, and his mastery is conflated with intelligence and “agency.” Thus, many works by disabled and autistic people are often marginalized in the art world because of facilitation.

“Collaboration happens by managing movement together” (Wolfond)

At dis assembly we are not interested in independence for its own sake, as autistic non-speakers know innately the need for, and our connectedness to each other and the world. There is no false performance as the independently-speaking neurotypical body. There is only collaboration and relational agencying (the gerund suggests intrarelational movement), as non-speakers will not conform.

While there is an attenuated attunement to others – as opposed to the notion that autistic people are “locked in their own world” or non-social, there is also a resistance to conformity. We enter into this relation of simultaneous engagement and avoidance as ways of subverting oppressive normativity while attuning to movement diversity as expression. Collaboration must therefore be mutual – more than one and more than human. Where some of us can support movement in a busy street, or to help activate movement, neurotypical collaborators are also moved by autistic gestures - ways of expression and ideas. We are moved in the studio by each other’s expressions with and without words. As dancers learn to dance, this way of support, communication and artistic-philosophical collaboration can only occur when it emerges together in experimental ways, for there is no fixed “method” that can reduce the dance of simultaneous, multifarious relations. It is important that we regard movement as expression with just as much regard as we do the writing. We do not privilege the supposed “intellectual” activity of writing over artistic activity and question the entire construction of intelligence as a humanist hierarchy.

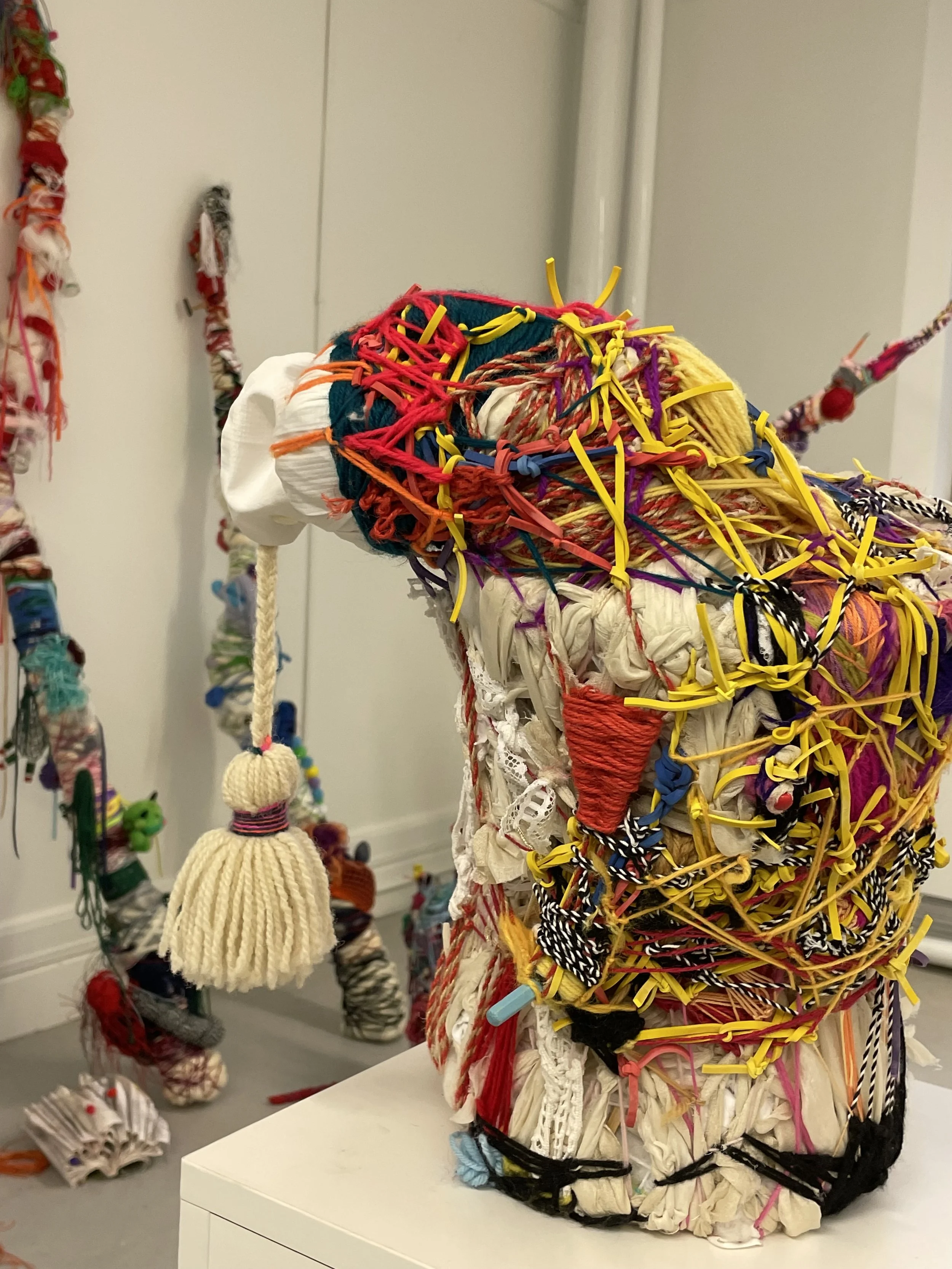

Adam Wolfond, Imane Boukalia and Isaac Wong are writers and poets inspiring a movement and material practices at our studio. Our Collective also consists of many speaking and non-speaking neurodivergent collaborators throughout North America who participate online. Often, we will experiment with materials to understand the richness of concepts that emerge through the languaging process. Or, movement and material practices enliven our language.

Languaging is also a movement, relation and a literary expression. Poetry is a movement and drawing, in our case, with autistic literary (or one might say aesthetic) rhythm and pace. Wolfond writes prolifically about movement and relation. He types on the keyboard creating sentences in three-wave patterns that blur transitions; a sfumato[i] where we feel the turn but find it difficult to make cuts. And so feels many an autistic body that merges with the “open” space; bodies that “can’t feel… arms and legs.” The feeling, the support, comes only in relation and with more movement. As much as Wolfond talks about his weightless feeling needing weight “to land” (Wolfond), anchoring with the support of another object or human, one wonders about the experience of a complex synesthesia with the body and perception as a blurry beingness, or a conjoinment with the world; not as the situated individual, but as bodies individuating in relation (Massumi), dis/assembling. Always more than one, we know we exist because of relation which, once again, is perhaps more attenuated in autistic expression.

The pandemic continues to pace us, as others learn about not only the paces many of us need, but also the many social inequities brought to light because of Covid. We shudder at the consequences from a lack of care and attention in “professionalized” settings. We must all find our way of pacing without the relentless push of a neurotypicality and neoliberalism.

Neurotypicality is more than a person – it is a way of thinking that has enforced a way of form, movement, and even way of learning and education that delimits diverse knowledges. Our neoliberal culture ceases to care, engage and take its time as it focusses on the bottom line. When the pandemic paced, our own polyrhythmic jams improvised a way of collaboration to make poetry, invite new ways of walking to discover the neurodivergent city, and to think of complex perception through wrapping, weaving together the relational, synesthetic qualities of rich autistic experience.

References:

Gins, M. Helen Keller or Arakawa. Burning Books, 1994.

Massumi, B. Parables for the Virtual. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2002.

[i] Sfumato, (from Italian sfumare, “to tone down” or “to evaporate like smoke”), in painting or drawing, the fine shading that produces soft, imperceptible transitions between colours and tones.

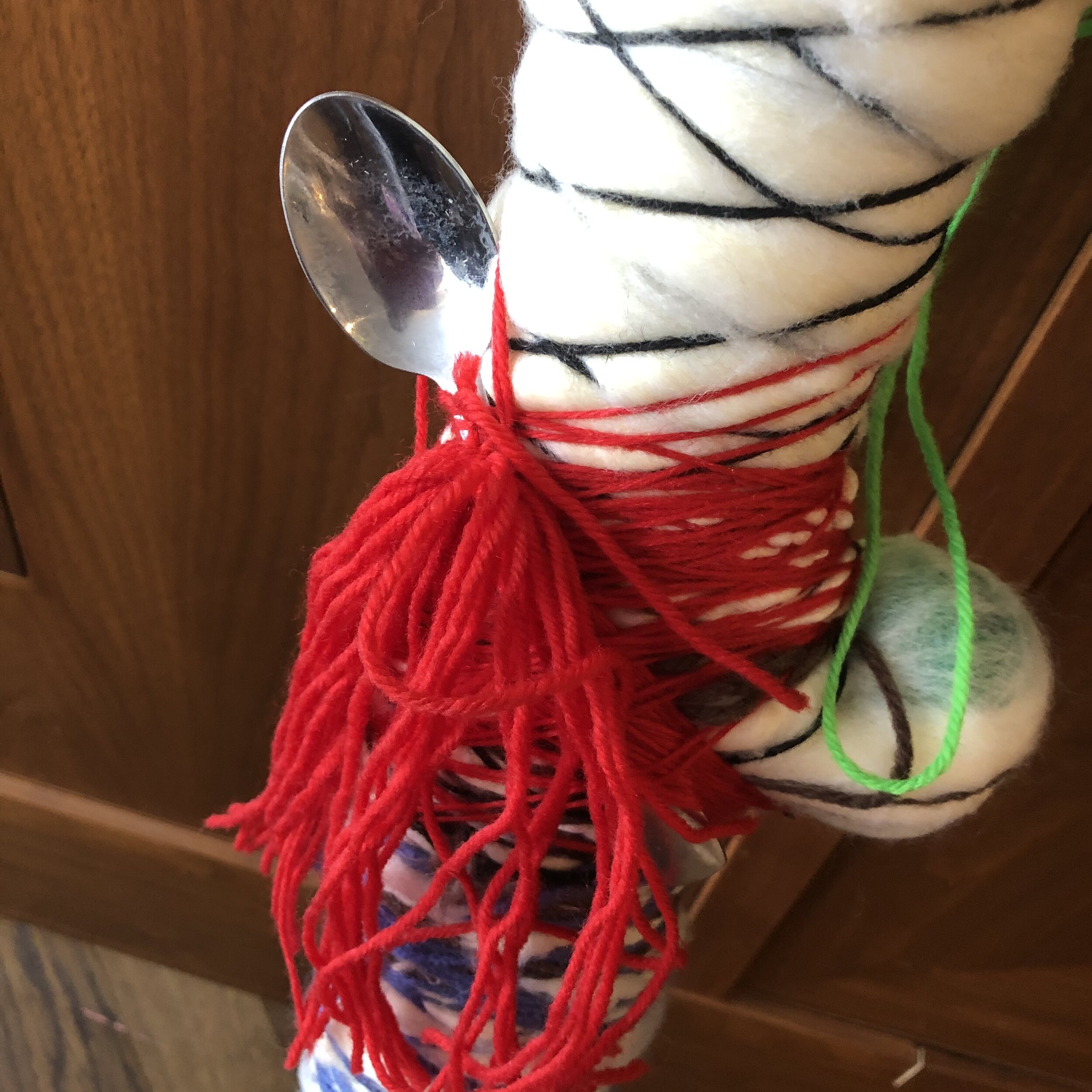

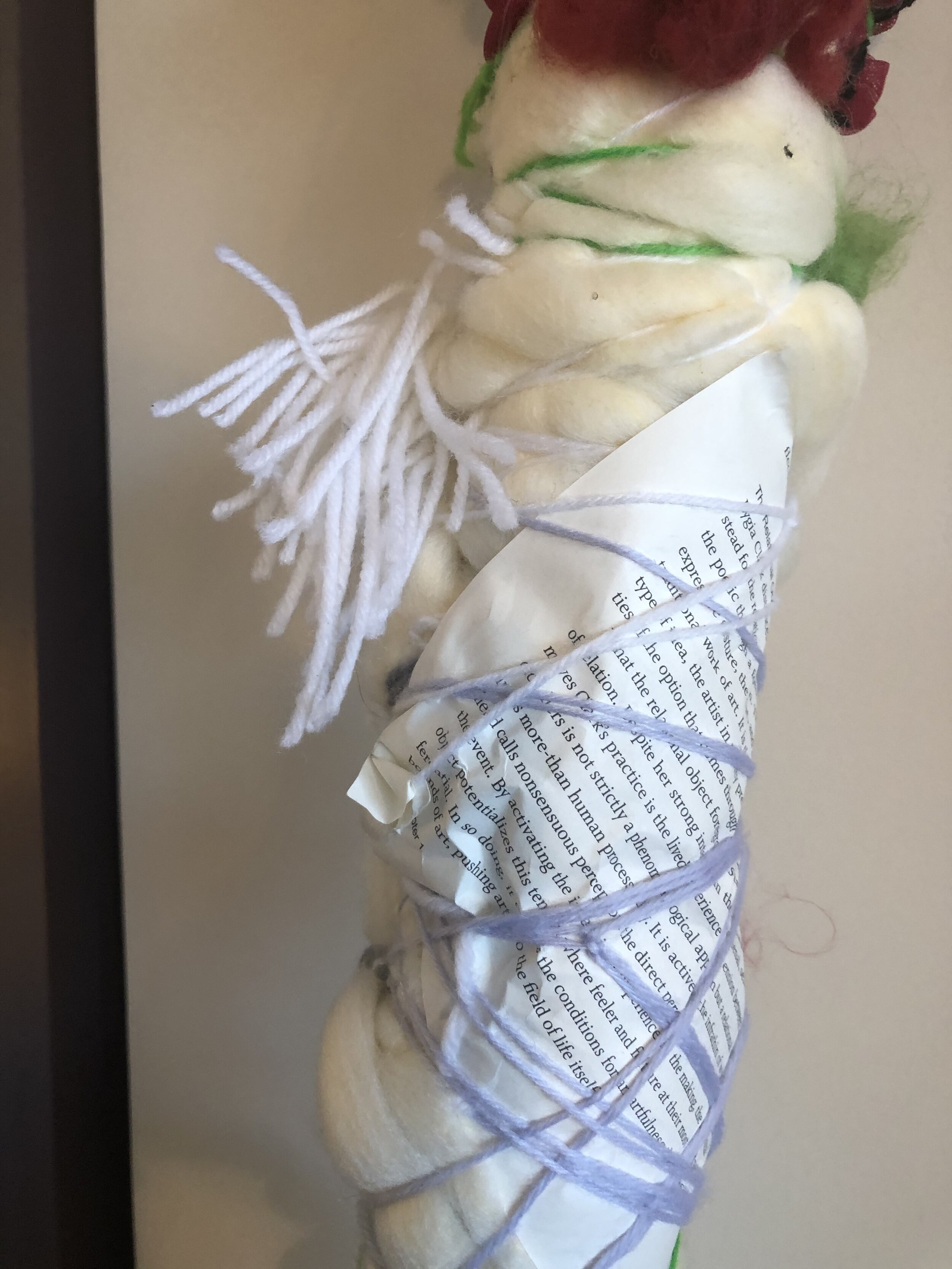

Poet Trees

During the pandemic, Adam and I walked more than usual. Typically on our walks, Adam seeks out sticks to twallow (his word that means shaking in front of his eyes), which help him navigate the busy visual field. Sometimes, seeking a way to weight his body to the ground, he gravitates towards heavy logs from cut trees or fallen limbs. He lifts them as high as his strength will allow. These gravitations and movements are a relation with the wood, the atmospheres, and multiple bodies. They are a way to be in engagement with the world.

His descriptions of the “atmospheres” are rich with synesthetic experience like the cars in the city “honking yellow.” Often synesthesia is described as a crossing of the senses as in “hearing colour,” but we contend that synesthesia and movement diversity is entwined and more complex. The phenomenon tends to be parsed rather than how Adam describes a sensorial smorgasbord occurring at once. Instead of drawing out each experience, Adam wraps and undulates feeling in a poetic sfumata where sensorial experience doesn’t just cross boundaries – it is literally blended and wrapped together like a ball of yarn. Unlike subtracting the details from perception, autistic perception is additive and detailed. So we wrapped the weighted poet trees with all the objects, sounds, colours, writings, objects, tastes (as in Tabasco bottles) that roll back up what science continues to unravel and parse, which we posit, cuts and reduces autistic experience.