ACCESS IS LOVE and LOVE IS COMPLICATED

AT CRITICAL DISTANCE CENTRE FOR CURATORS

PRESENTED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH TANGLED ART+DISABILITY

OCTOBER 3–DECEMBER 8, 2019 / Opening Oct 3rd, 6–9 pm

CRITICAL DISTANCE and TANGLED ART+DISABILITY are pleased to present ACCESS IS LOVE and LOVE IS COMPLICATED, an exhibition and event series featuring Vanessa Dion Fletcher, Kat Germain, Wy Joung Kou, Dolleen Tisawii’ashii Manning, Andy Slater, Aislinn Thomas, and Adam Wolfond and Estée Klar. This program is co-curated by CDCC Education and Accessibility Coordinator, Emily Cook, and Tangled Art + Disability Director of Programming, Sean Lee and represents the next level in our ongoing series of programs providing opportunities for curators and artists to consider new and more collaborative aesthetic and conceptual approaches to accessibility within and beyond the gallery context.

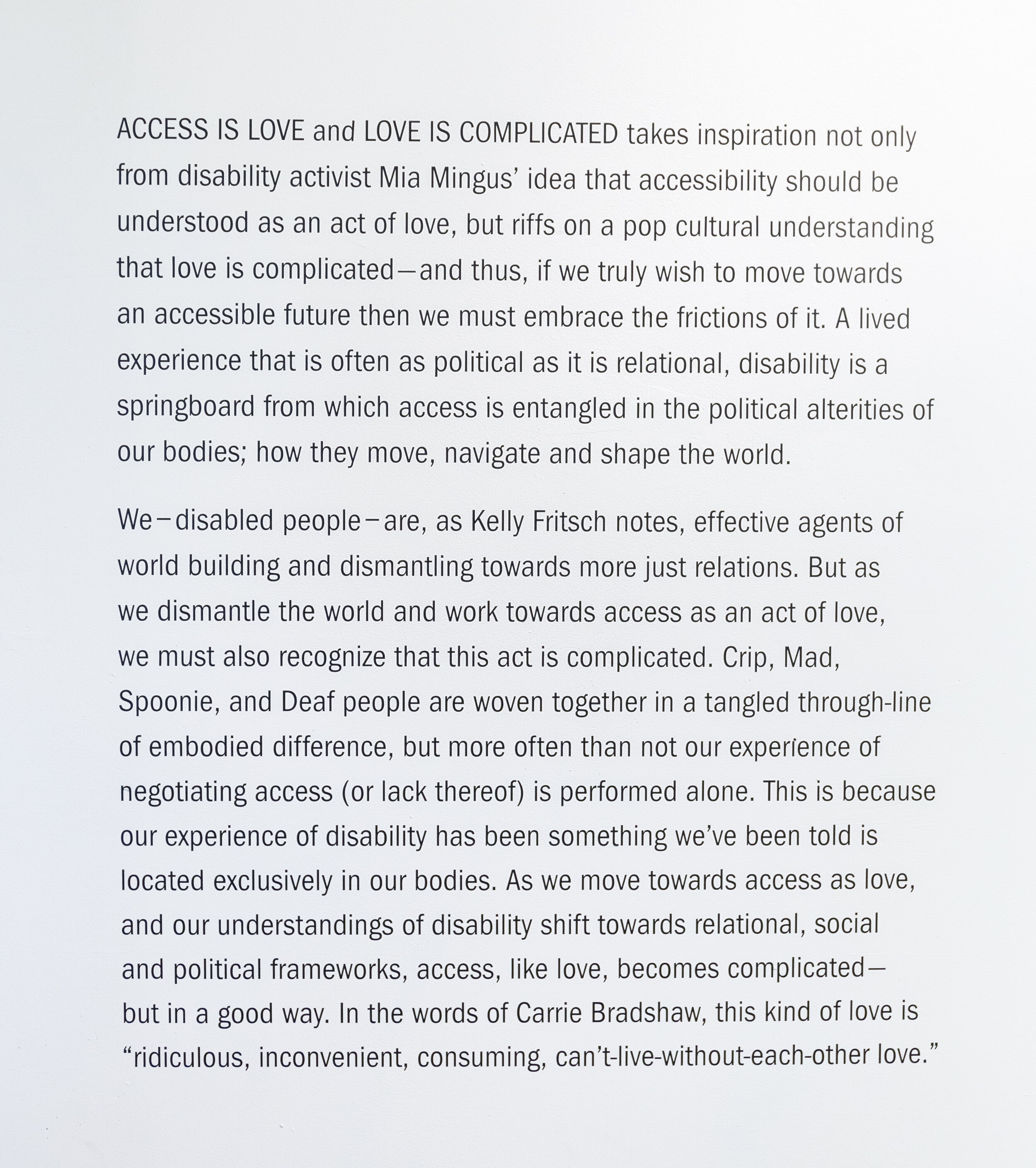

ACCESS IS LOVE and LOVE IS COMPLICATED takes inspiration not only from disability activist Mia Mingus’ idea that accessibility should be understood as an act of love, but riffs on a pop cultural understanding that love is complicated—and thus, if we truly wish to move towards an accessible future then we must embrace the frictions of it. A lived experience that is often as political as it is relational, disability is a springboard from which access is entangled in the political alterities of our bodies; how they move, navigate and shape the world.

We–disabled people–are, as Kelly Fritsch notes, effective agents of world building and dismantling towards more just relations. But as we dismantle the world and work towards access as an act of love, we must also recognize that this act is complicated. Crip, Mad, Spoonie, and Deaf people are woven together in a tangled through-line of embodied difference, but more often than not our experience of negotiating access (or lack thereof) is performed alone. This is because our experience of disability has been something we’ve been told is located exclusively in our bodies. As we move towards access as love, and our understandings of disability shift towards relational, social and political frameworks, access, like love, becomes complicated—but in a good way. In the words of Carrie Bradshaw, this kind of love is “ridiculous, inconvenient, consuming, can’t-live-without-each-other love.”

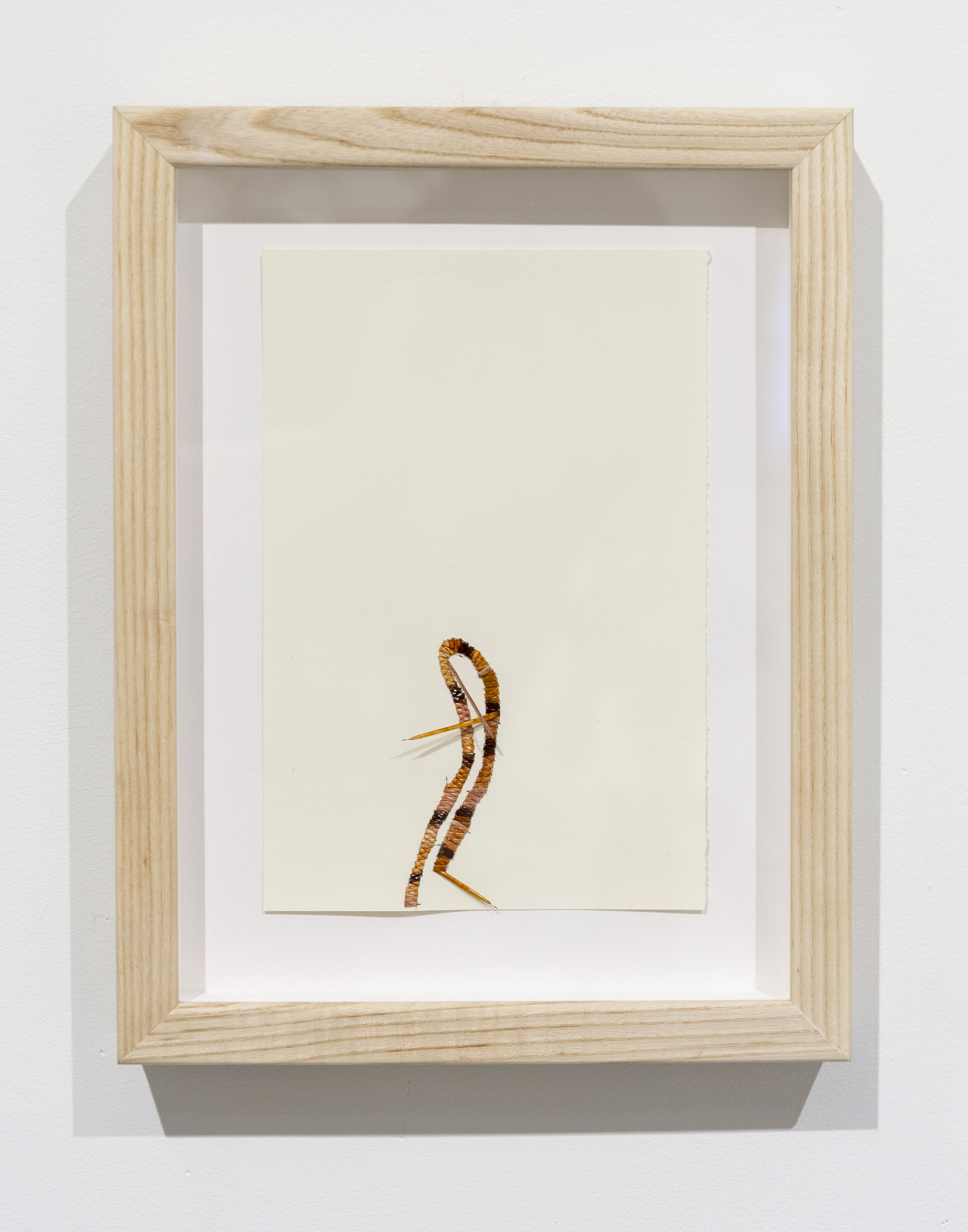

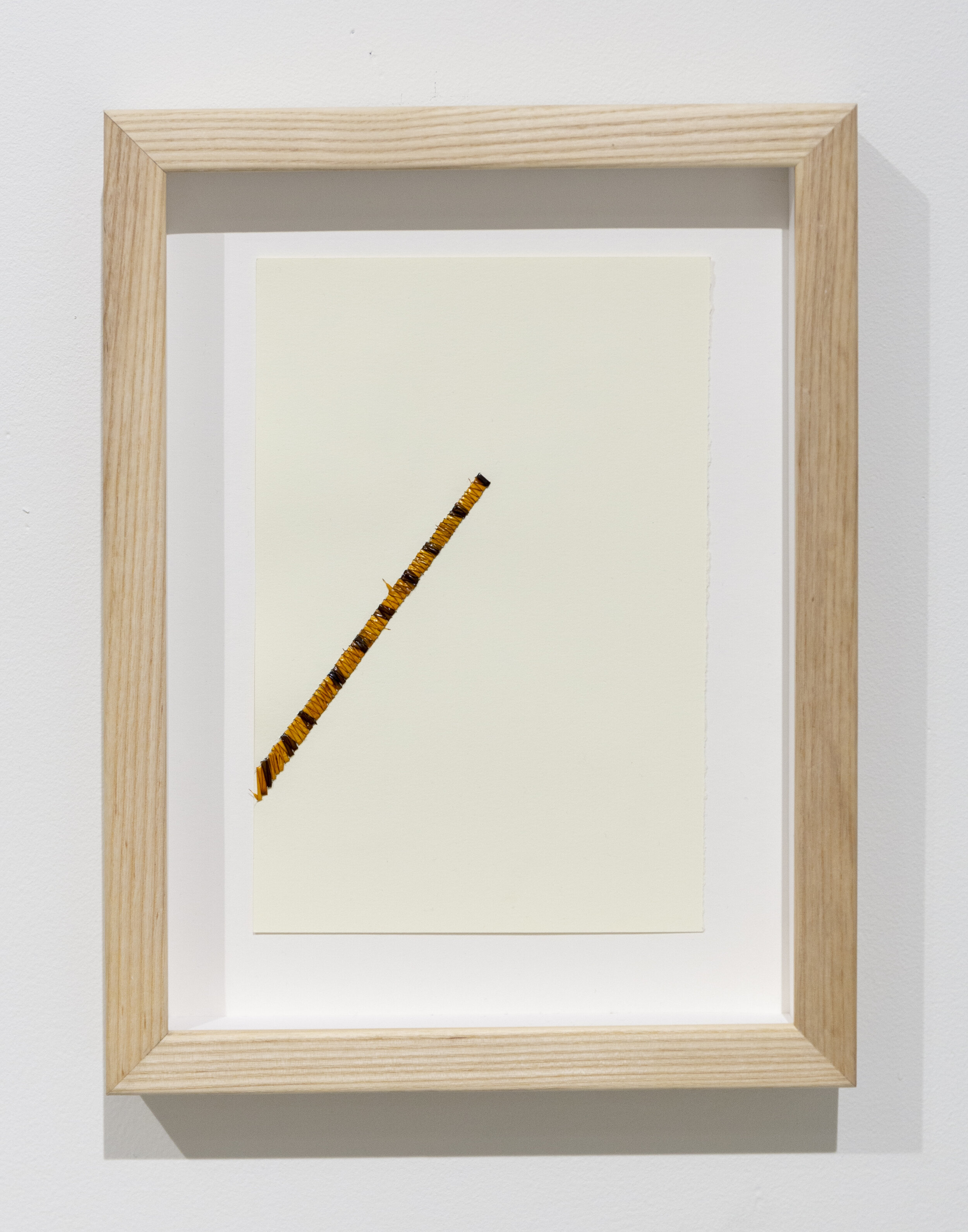

S/Pace

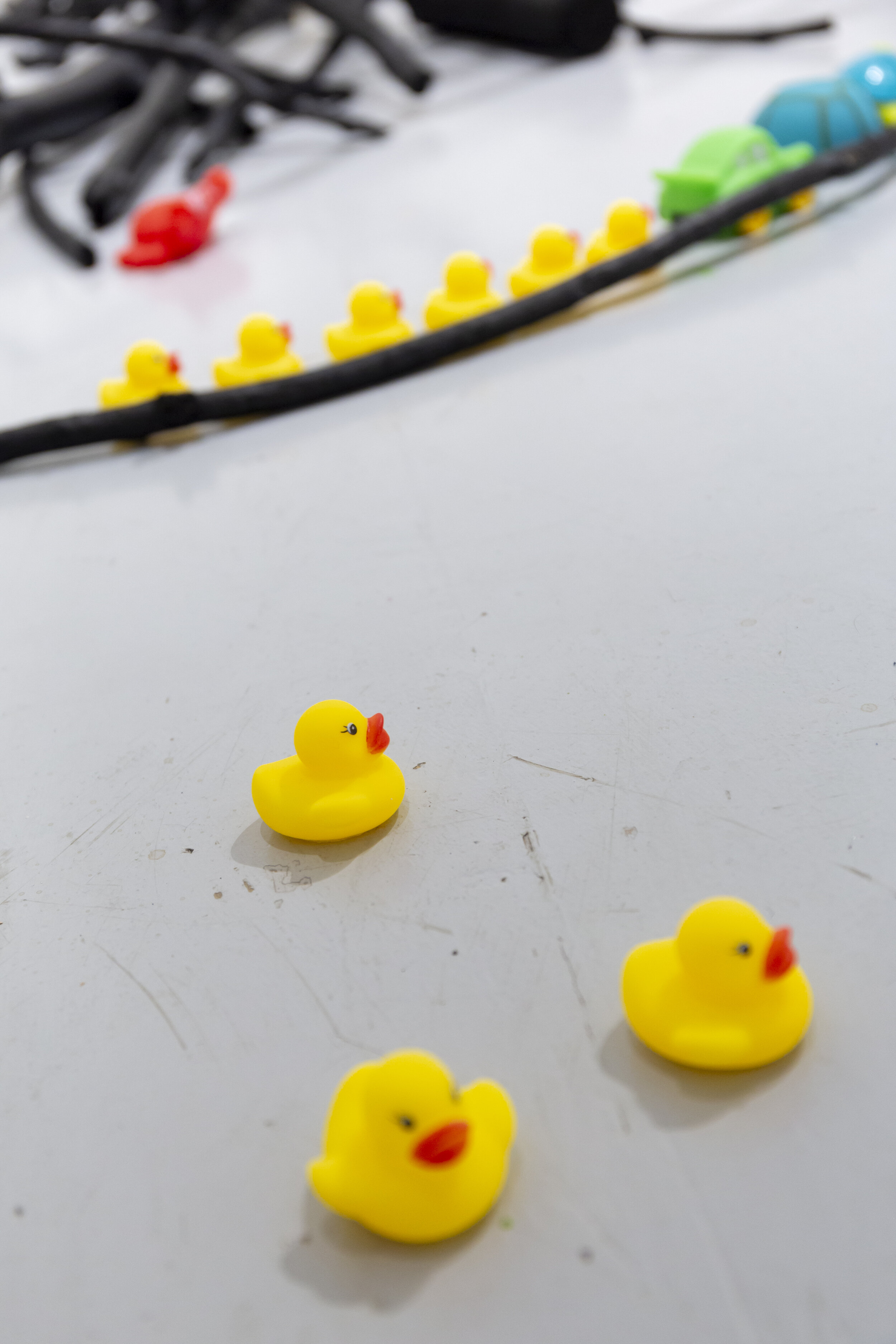

Adam’s relationship with the stick is explored in an upcoming film S/Pace, where he explores pacing with sticks to feel and navigate his body within it. For Adam, he explains how he “cannot feel the ground of his feet,” and moves with objects - thin sticks, heaving sticks - for this grounding, suggesting incorporeal relation: intrarelation.

I want to think with sticks. Thinking with sticks is like thinking about open eager space and the rows of walks I take. The wanting teetering walks think about how the sticks are going toward the next one. The desire thinks the sticks assemble the pattering honing in and offering me good help.

Time is perceived by the appreciation of language but I am pace of my body and not language. My body is pacing is the task of feeling my body and the feeling of the pace of the environment I am feeling. The work is answering in a logical way about the amazing senses but I am not sensing the same way. I am always feeling a lot of things and it’s hard to have concentration when I am not able to be a the talking-table but in the feelings of the world.” (Adam)

“I am the open feeler who feels too much”

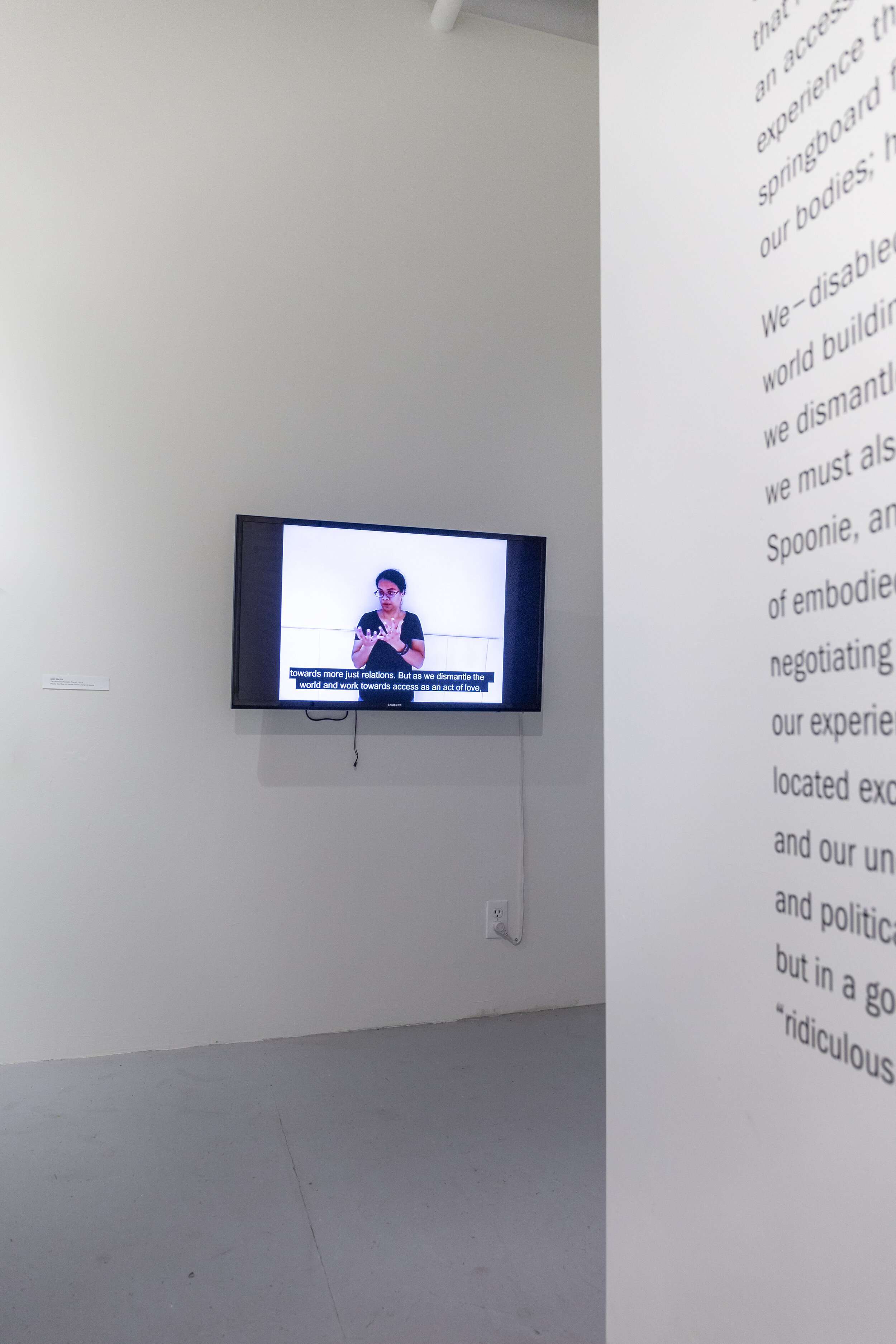

This exhibition film installation accompanies work with Adam regarding S/Pace where Adam explores his relation with rhythm, and space. Pace is the way Adam says he “answers” space - of tapping toys and waving sticks, or tapping them on his wrist. Adam declares that “I can see the blast of the whole not like you” and that the visual field is always moving. Waving sticks and tapping/squeezing rubber bath toys are as visually pleasing as much as self-adaptive in order to move and transition through space itself. Adam writes:

The body is always having movements and I am mobile having objects with me all the time. Boy needs objects to move. I see the objects and focus on assembled parts in the environment like a house and not the door and because I don’t see the door I manage by doing lots of amazing things like pacing my movements to the same way as my assistants. I see the whole but not the same whole as other people. They are not able to see the blast of the whole like I do. They can see the school but I can see everything gathering in the hallway moving; the forging movements of movement. Van Gogh is not like how I see but I manage moments of movement like a painter who is landing the boy’s thoughts and perceptions.

A collaboration with myself, artist Ellen Bleiwas and filmmaker, Eva Kolcze, Adam explores his relation with sticks and rubber bath toys as they “answer” the space or the pace of “fast talkers.” Ticcing as a way to feel the world denotes proprioceptive diversity as Adam notes that,

[h]ands other than legs space good feelings because my hands are the name of mastery other than the legs. The away feeling is hard to manage, and the hands are the way I can walk. The away feeling is the way of naming the way my legs feel and I do not feel them. I want you to understand that I am always trying to feel.

Adam alludes to what Arakawa and Gins name vitality, a way of spacing space that is not self-same as in walking with legs. Madeline Gins noted that “in order for something to be thought of, or for an object to be perceived, something (some event) will need to be adhered to, no matter how briefly” (Gins, 1994, 10). She uses the term to “cleave” as to adhere to, and simultaneously “be cut apart” (9). “How do I move? I can only move by eating up or dissolving where I am. I (anyone) pull in with a bright gulp what is to come next (10-11). When the hesitating, ticcing, the body also seeks to land towards its next move. “What happens to your position when I move, when I move a wall, or change the angle of the floor? What happens when the sidewalk always feels it is moving? (Ibid). In the hesitation, the tic, the wave of the stick, the tap of the toy, Adam cleaves and prepares to move forth. “I can feel my arms and legs but not the ground beneath my feet,” he writes. Adam writes towards a leaky sense of self in the world, a “thinking-feeling through a body that is always moving” (Adam); a way of becoming. Where Arakawa and Gins experiment with bodies in space as a form of vitality (of life-living) “to reconfigure oneself so that you can stay alive ongoinginly” (16), Adam’s vitality is through movement in relation - as hands, twirls, tics, taps and even my hand on his back to initiate movement when he cannot. Adam:

Ticcing through the world is like touching it… I feel the world too much so open bothersome work is to feel inside pandering to language. The work is to feel the world that is touching me.

This is neurodivesity as relation.

Reference:

Madeline Gins. Helen Keller or Arakawa. Burning Books, 1994.